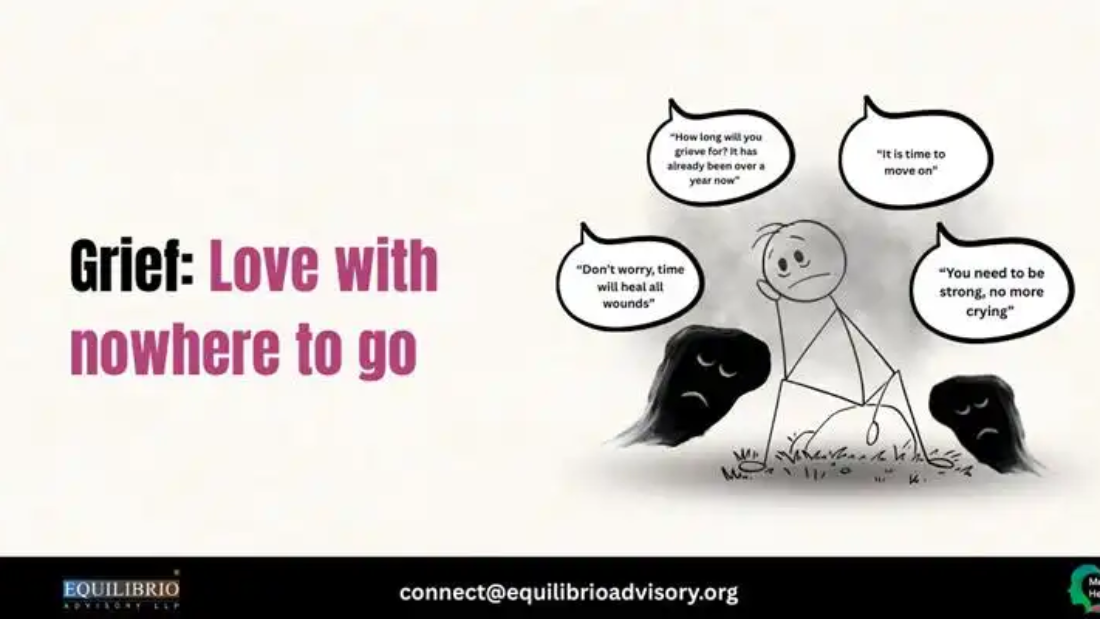

“Don’t worry, time will heal all wounds”

“You need to be strong, no more crying”

“How long will you grieve for? It has already been over a year now”

“It is time to move on”

“Grieving is not going to bring back the dead, snap to it and get back on your feet”

Most of us may have experienced loss at some point of time or the other, and hence may find the experience of grief, or intense sorrow that accompanies loss relatable or familiar.

In those times, we may recall having heard the lines above directed at us.

These statements are ever present at times that hold grief within them – especially condolence meetings, or at the final rites of people. We have heard them so often, it’s normalized of offer these lines for “comfort”. As a way to, perhaps, encourage a person to look to the future. These statements may even be a response to one’s own discomfort at overt expressions of grief.

But have you ever stopped to think about the impact such lines may have on the person grieving?

This article will support you to develop a nuanced understanding of Grief as an experience and support you to explore a range of responses to support you to respond when you are engaging with someone who is experiencing grief.

Understanding the experience of Grief:

Grief is a complex response to the experience of profound loss. It is an intense & sometimes overpowering emotion of deep sadness.

Grief arises in response to loss of something significant and valued – loss of a loved one, a way of life, the loss of one’s hopes and dreams or from a terminal diagnosis received by a person themself or by someone they care about. Grief is both, a universal experience and a deeply personal one.

According to psychologists processing grief may occur through stages.

Elisabeth KĂĽbler-Ross was a Swiss American psychiatrist who was a pioneer in near-death studies, professor and author of several award-winning books developed the 5 stages of grief. They are as follows:

Let’s take a deeper look at these Stages of Grief:Â

Denial: This initial stage involves a refusal or inability to accept the reality of loss. It serves as a buffer mechanism to buffer the immediate shock. Individuals may feel numb or refuse to believe that the loss is not true, often thinking that things will return to normal.Â

Anger: As the reality of the loss sets in, feelings of anger may arise. This anger can be directed towards oneself, others, or even the deceased. It is a natural response to the perceived unfairness of the situation and can manifest in various ways. Â

Bargaining: In this stage, individuals may attempt to regain control by making deals or bargains, often with a higher power. They might dwell on “what if” scenarios, wishing they could change the outcome of the loss. Â

Depression: This stage is characterized by deep feelings of sadness and regret. Individuals may feel overwhelmed by the weight of their loss, leading to a sense of hopelessness. It is a normal part of the grieving process, allowing individuals to confront the reality of their situation. Â

Acceptance: The final stage involves coming to terms with the loss. Acceptance does not mean forgetting or being okay with the loss; rather, it signifies a recognition of the new reality and the ability to move forward with life. Â

Grief is not a single emotion – it is the language of the heart, when it has loved deeply and lost, often a response to a catastrophic tragedy which has altered life forever. There is no linear movement to grief, no checkboxes or timelines. There may be some back and forth across the stages as well. Sometimes it arrives like a tsunami, sometimes, it is dull ache in the heart when you see a familiar object of the departed.

Collective grief is when an entire community, group, nation, or even the world mourns together — a shared sorrow in response to unimaginable loss. It often emerges after large-scale tragedies: war, natural disasters, pandemics, genocides, or catastrophic accidents like the AI plane crash in India.

In such moments, grief ripples far beyond those directly affected. The loss becomes part of the social fabric, altering how we view safety, humanity, and the fragility of life.

First responders, who rush toward devastation when others flee, carry a unique weight. Their role requires holding space for grief while suppressing their own. This experience often leads to delayed trauma, as the mind files away the experience and delays immediate reactions to what is being witnessed, to be able to cope in the moment.

Collective grief can be heavy, especially since there may not be many spaces to action change, process the grief or even name it. In coming together as members of a shared community — at vigils, memorials, in shared silence and even online platforms that acknowledge and validate such shared grief – healing can begin.

Grief and other emotions: Understanding GuiltÂ

Grief is often mixed with guilt – “Why was I left alive”? “Should I be going to this office get together?” “It is wrong of me to like someone when my beloved has died” “Did I do enough to save him/her? Maybe I should have taken them to a different doctor” Questions like these tend to haunt the minds of the survivors.

Grief and guilt often walk hand in hand—grief as the ache of loss, and guilt as the echo of all the “what ifs” and “if only.” It’s painfully human to look back and wonder if we did enough, said enough, were enough. Especially when we’re grieving someone, the mind tends to retrace steps, searching for missed signs or moments that might’ve made a difference.

Sometimes guilt stems from surviving—being the one left behind. Or from feeling joy again, as if healing dishonours the love we lost. But here’s a quiet truth: feeling happiness doesn’t mean forgetting. Guilt may try to convince you that sorrow is proof of love—but love is patient, forgiving, and spacious enough to hold both sadness and peace.

Grief and the Intersection of Neurodivergence

The manifestation of grief and the ability to reach out for support can be further complicated by the presence of neurodivergence. Communication and social differences, sensory processing differences and emotional regulation differences can make the experience and expression of grief very unique for neurodivergent persons.

Communication differences – Several neurodivergent persons communicate in non-traditional ways, other than verbalizing their feelings. Many can choose words, making art or resorting to movement to create an outlet for their feelings. Communication differences can often make it hard to reach out for help, when a person is dealing with grief.

Emotional Regulation differences – Alexithymia is a unique trait that is often present in the autism spectrum. Alexithymia refers to the inability to describe or identify feelings. This can often lead a neurodivergent individual to struggle with feeling their emotions, and can lead to a propensity to intellectually break down their emotions, which can delay the grieving process.

On the other hand, many neurodivergent persons experience a depth of emotional intensity that can cause overwhelm and shutdown. For instance, the death of a virtual friend—whom the neurodivergent individual never met in person—might trigger a sense of bereavement that would be traditionally associated with the death of a family member.

Grief Time – Although Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s stages of grief is the popular model to understand the timeline for grief, the framework may not apply to the experiences of neurodivergent persons. There is an understanding of experiencing time differently within the disabled community. This understanding also lends itself to the non-linear time of experiencing grief.

For instance, the death of a loved one that happened a decade ago, might strike a neurodivergent person with fresh emotional intensity; or they might have a delayed reaction of years to feel grief at the loss of something valuable.

Sensory sensitivities – Sensory processing depth is often greater within a spectrum of neurodivergent persons. This might manifest as an aversion to loud noises, bright lights, strong smells, all of which might be present in a funeral.

Often in the Indian cultural context, funeral rites of passage go on over a week, this can lead to sensory overload for a neurodivergent person and lead to a meltdown. Sensory sensitivities can be even triggered on the experience of emotional intensity, which is often a strong sensory experience as well.

Executive differences – Executive differences refer to the different styles of executive functions—like planning, working memory, organizing, impulse control, starting a task—within neurodivergent persons. Many neurodivergent persons stick to routines or structures to ground themselves. A loss of a person of any other kind, can disrupt their routine which can lead to anxiety and distress. In this case, a common coping mechanism, is hyper-focusing on a different task or goal to avoid the feelings of grief, or disassociating from their current environment.

It is important to recognize the different ways in which grief can manifest within the neurodivergent community. Expecting the expression of grief to adhere to a social script that has been popularized in pop culture leads to limiting support—that can be extended when different expressions of grief are acknowledged.

Some practical tips on how to support a grieving individual:

As a good friend or a close relative to someone who has suffered loss or received news about a critical illness just verbal reassurances will not be enough.

Making “helpful” suggestions and comments about moving on and looking for the silver lining also won’t cut it. Supporting someone who is grieving requires presence, patience, and compassion — not solutions. The process of grieving is deeply personal, and there’s no “fixing” it.

So, what can be helpful? Below, we’ve listed some practical ways you can support the people around you as they navigate their experience of Grief.

- Create a safe space for the person: Don’t judge a person’s journey through grief. Statements like – “But it was only a pet”, “It’s been years do you really still feel this”, “Who knows what would have happened if the child was born, maybe this is a blessing” can really invalidate a person’s experience and make it harder to reach out for support.

- Avoid comparisons: Do not compare their loss with your own; or compare their manner of grieving with that of another person. Each person’s grief is unique and if you end up taking about your own loss, you will be trivialising their grief.

- Listen actively without trying to “fix it” or find a solution: Provide a safe space to the person to cry, speak or vent about the situation. Do not offer an opinion or suggestions. Just listen with empathy. This can be very cathartic for the griever.

- Talking or sharing memories: Encourage sharing memories and photos of the deceased which will help the survivor to remember happy times rather than focusing on the death. It may also help them to talk and vent about the occasion as well as the person, thus lightening their emotional burden and creating a space to process their grief without the feeling of being judged.

- Offer practical help: The grieving person might be feeling overwhelmed. Offering to cook a meal, drop children for classes or to school, offering to watch them while they play outdoors, running errands etc. will be huge help.

- Become neuro-affirmative in your approach: Try to educate yourself around the intersection of neurodivergence and grief. Learn how you can support a neurodivergent person manage sensory or emotional overwhelm. Be open to them communicating their grief at their own pace and / or in a non-traditional manner.

- Be present: Offer consistent support as per their needs, after checking with them, e.g. picking up their kids from school, providing lunch, a before bedtime phone call to talk, accompanying them to a therapist’s etc..

- Check – in regularly on them so that they know they are not alone by calling, messaging and if you share a close relationship dropping in on them

Sometimes all you need to say is “I am here for you whenever you need me” and mean it. These words expressed sincerely will make a lot of difference to the grieving person. A simple hug (with consent), a squeeze of the hand, an arm around the shoulder makes a world of difference. Helen Keller famously said,“What we once enjoyed and deeply loved we can never lose, for all that we love deeply becomes a part of us.” Perhaps that is what grief teaches us best – how not to forget but to carry love forward.Â

Remember you are not alone. Your feelings are valid, and it’s important to reach out for support. If you or someone you know is experiencing the intensity of grief, please reach out for support.

Written by Asha DSouza and Rosanna Rodrigues

Cart is empty

Cart is empty