Each year, during men’s mental health month, we put out a call to remind all those who identify as men, to reach out for support.

Table of Contents

In this November, the theme being spotlighted for International Men‚Äôs Day is “Positive Male Role Models,” which also lends itself to fostering open conversations about men’s mental health and creating supportive environments where men can thrive.

The reason behind the spotlight being on speaking up and reaching out when it comes to men’s mental health lies in the data, and the lived experience.

While men also experience mental health concerns, the social expectations and conditioned personal understanding of masculinity linked to “Strength” and “Endurance” often lead to repression of emotional experiences, and act as barriers to accessing support.

One look at the statistics provides evidence for this pattern:

- According to the Accidental Deaths & Suicides in India 2021 report by the National Crime Records Bureau, men make up 72.5 per cent of suicide victims, a staggering difference compared to women. In 2021 alone, over 73,900 more men than women died by suicide.

- Men are less likely to access psychological therapies than women: only 36% of referrals to NHS talking therapies are for men. (NHS UK)

- Men are nearly three times more likely than women to become alcohol dependent (8.7% of men are alcohol dependent compared to 3.3% of women (Health and Social Care Information Centre)

- Majority of the callers on the hotline are men between the age group of 18-45. Most have reported experiencing sleep disturbances including chronic sleep deprivation, insomnia, sleep apnea, narcolepsy, and restless legs etc., all symptoms that usually are noted alongside mental health concerns (Tele Manas)

Moreover, there is a debate about the under-reporting of mental health concerns when it comes to men. This is due to the social stigma attached to vulnerability, and toxic masculinity that values certain ways of expressing emotional distress and frustration.

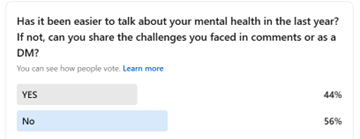

To explore the reality of this, we at Mental Health At Work, powered by Equilibrio Advisory LLP, put out this poll question on our LinkedIn Platform. During June which is observed as Men’s Mental Health Awareness Month (US), we asked those who identify as men a simple question:

Has it been easier to talk about your mental health in the last year?

56% of those who responded, replied – NO.

Introducing the MHAW initiative:

In order to understand a little more about men’s lived realities, barriers to accessing support, their perception of mental health and expectations of support, we attempted to engage in a conversation with the men around us.

We asked men in our social circles two broad questions,

- “What does mental health mean to you?”

- “What kind of support would be helpful to you?”

We got 17 responses from men, who were in a wide range of ages from 24 to 70. The majority of the men were in their 30s, and there was a range in their professional backgrounds as well. Our participants came from educational, legal, business, banking, marketing, artistic and design backgrounds.

It’s interesting to note, that several of the men we reached out to chose to ignore, or not to comment or engage in a conversation around their mental health at all.

Below we are sharing some of the insights we gleaned from this exercise.

“What does mental health mean to you?”

When it came to the first question regarding their personal understanding of the definition of mental health, we could locate a few common metrics of well-being that our group of participants were identifying and holding as important.

We were able to isolate several elements that were being referenced by the people who engaged with the questions we posed.

Some elements focused on cognition particularly “one’s ability to function”, “solution-based thinking”, “work efficiently”, “Make decisions”, “Will” / “Strength of mind” and “being conscious”

Some identified spiritual aspects of wellbeing and even noted that mental health does involve “Purpose in life”. While some also identified factors that impacted mental health, drawing out what robust mental health did not include – like “Stress”, “Interpersonal conflict”, and “Mental noise”.

Some elements that bubbled up valued positive social connection as a metric of wellbeing as well.

Several participants indicated that resilience, “the ability to cope”, “manage emotions” or “Letting go” was a significant aspect of mental health.

Some of our participants also linked or contrasted mental health with physical health as well as a sense of accomplishment, or progress.

Most interestingly, however an overwhelming frequently referenced metric of wellbeing was linked to emotional states. While factors like freedom, happiness, confidence featured in their responses, but the responses that were most common were

- Peacefulness, Calmness, Equanimity

- Balance

The survey found that almost all of our participants were aware of the concept of mental health, and were able to connect it to their own lives. There were also links to larger social systems and frameworks, particularly consumerism was noted as detrimental to mental health. Most participants seemingly located the onus for mental health within the self, with a few mentioning therapy / support.

One participant admitted that mental health as a concept meant nothing to them. Another mentioned that familiar situations, even if they are negative, are easier to deal with than adapting to new situations, which brought in the experience of stress.

“What kind of support would be helpful to you?”

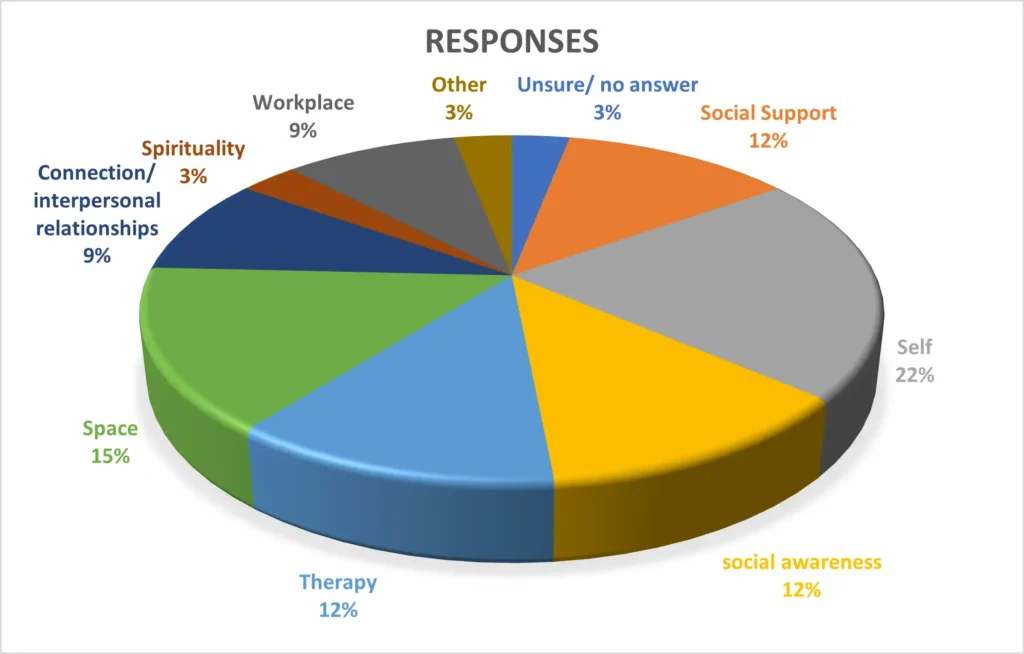

With the second question, we were trying to gauge how men view support and tried to explore if there was openness to reach out and seek support when it comes to aiding their mental well-being. In the responses we received, a clear pattern emerged.

The most common responses that came for spaces of support were about reliance on oneself, with 22% participants mentioning it.

This was followed by the abstract idea of ‘space’ that 15% of the participants mentioned as helpful. Some qualified this space as one of emotional safety, some as a reflective space, a space where the participant could “let our guard down” and be vulnerable.

Several participants mentioned social connections and familiar interpersonal dynamics, including friends and family, as spaces of psychological safety.

Some participants also referred to a larger social awareness that is required to shift and create change that is supportive of mental health and wellbeing for men as well – particularly when it comes to discrimination (owing to marginalized identity) or the social idea that men cannot or do not share their emotions.

9% of the participants mentioned support at the workplace could be supportive when it comes to their mental health journey.

12% of the participants identified therapy as a possible space of support.

Finally, there was one participant who could not think of any possible support spaces.

Our reflections into what has emerged:

It is interesting to note that most of our participants had a general perspective of what mental health means. Some of them could also identify a connection between mental health and physical health, and the need for mental hygiene. They could see a connection between poor mental hygiene and physical illness.

Some of them reckoned that good mental health could help them cope with their internal mindscape and allow them to ‘let go’ or cope with hardships. One of our participants could even find a connection between robust mental health and the ability to be vulnerable.

Some of our participants also identified that good mental hygiene is linked to smooth cognitive functioning, the ability to think analytically and come up with solutions, the ability to make informed decisions, to perform well in their professional sphere etc. However, one participant noted that they are uncertain of what mental health implies.

Perceived barriers to mental health and support:

No interrogative exercise would be complete without looking at the converse side. Therefore, we took note of the factors that the participants identified as clear barriers towards mental wellbeing and accessing support. The most common factor that was located by our participants as a barrier to mental peace was ‘stress’ or ‘anxiety’ with 33% of them naming it. A couple located barriers within interpersonal conflicts. Some participants mentioned juggling ‘day to day challenges’ as places of discomfort.

20% of the participants mentioned the anxiety of dealing with new or unexpected situations, and a couple could identify internal emotional distress (‘inner demons’) as a cause of poor mental hygiene. Finally, some of the participants located barriers to mental equilibrium in the larger systems of capitalism, consumerism, globalisation and how it has created more ‘fast paced’ lifestyles. One participant also agreed that ‘lack of time’ for reflection and pausing also lead to poor mental health outcome.

When it came to seeking spaces of support, around 41% of our participants stated that they would only rely on their individual resources for support, instead of asking for external support. However, 45% of our participants belied an understanding of what can be possible hurdles towards seeking support. They noted gender stereotypes where men are expected to not belie any emotions or are seen to be providers to their family (“rock pillar of the household”) that can become significant deterrents. These stereotypes coupled with the gendered socialization of men to not seek help and cultivate self-reliance can make it difficult for them to be open about their vulnerabilities and reach out for external support. A couple of participants also remarked that social judgements based on ‘faith, gender and financial status’ can also create stigma and lead to poor mental hygiene within certain men.

Another aspect that emerged was a connection between mental health and will power. While one of our participants observed that those who need to seek help with therapy might be lacking in will power, another participant was of the view that men are taught ‘fortitude’ by putting up walls. He further stated, that breaking down these walls could lead to a liberating experience.

We hope this reflection piece has created space to ponder on – what does mental health and support really look like for the men around us?

Our intention behind this exercise was to bring a spotlight to lived experiences. Through this small initiative, we have been able to encourage more people to talk about their mental health and wellbeing, especially to the people closest to them – thereby chipping away at the barriers that inhibit us from experiencing wellbeing and fullness and get in the way of accessing support.

In closing, we would like to leave you with a soft reminder. Remember, you are not alone. Your feelings are valid, and it’s okay to feel what you are feeling. But in a larger culture that does not allow us time to pause and reflect or learn the need for emotional regulation, it’s all the more crucial to be able to reach out for support.

Written by Rosanna Rodrigues &¬ÝUsri Basistha

Cart is empty

Cart is empty